The respected Malay history and culture researcher’s debut book celebrates not just the cuisine of the Malays, but also the people and culture of the Malay Archipelago

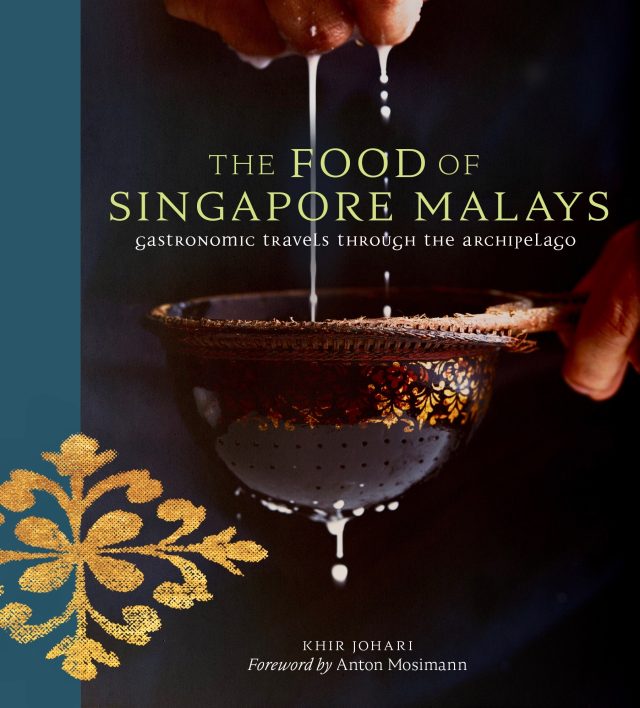

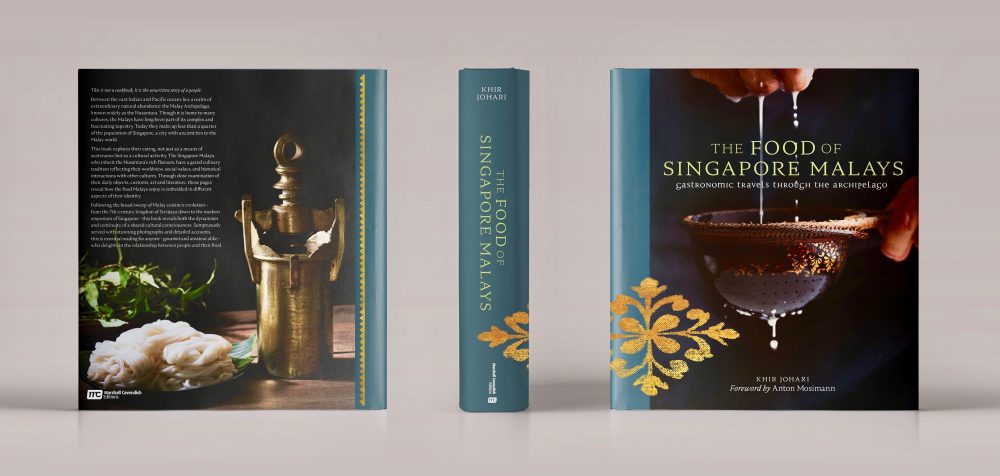

Singapore, 25 November 2021 – “The Food of Singapore Malays: Gastronomic Travels Through the Archipelago” (Marshall Cavendish International) launches on Monday 29 November 2021. Written by Khir Johari, the 624-page book explores how history, geography and cultural beliefs have shaped and influenced Malay gastronomy – and Singapore’s role as a creative kitchen hub in this culinary evolution.

Khir’s first book is 11 years in the making and includes over 400 stunning photographs — mostly shot by photographer Law Soo Phye — of food and culture around the region as well as 32 detailed recipes for key Malay dishes. These range from classics like sayur lodeh and mee siam – a uniquely Singapore Malay dish – as well less well-known dishes like pindang serani, a light, tangy tamarind-based fish broth that is served at home.

THE REAL ROOTS OF MALAY CUISINE

Packed with research and meticulous detail, “The Food of Singapore Malays” traces the evolution of Malay cuisine in four comprehensive sections that guide readers to dip in for bite-sized bits of information, or indulge in a leisurely read if the mood strikes. Along the way, Khir takes readers on a journey through centuries of Malay food history from the 7th century to the present day, with Singapore at the heart of his narrative.

The book kicks off with People, Space and Place, a section that expands our perspective of

Singapore’s history by exploring stories of Singapore Malays. Alongside a narrative of the region’s burgeoning importance as a maritime hub, Khir discusses the many definitions of Malay that exist across the Malay Archipelago. He also focuses on the significance of Kampong Gelam, Singapore’s oldest Muslim quarter dating back to 1819. Khir grew up in the historic Gedung Kuning (Yellow Mansion), once an annex of the royal palace of the Sultan of Singapore. In this sprawling home, his four-generation family lived and some of Khir’s earliest food memories were defined.

Indigenous Ingenuity, the next section, shines a light on the almost-forgotten skill of foraging and how it has shaped Malay cuisine. Foraging, considered the oldest means of acquiring sustenance, requires little to no specialised tools and demands less exertion than agriculture and hunting — making it accessible to a wide spectrum of the community. The Malays developed a sophisticated understanding of how to forage and gather ingredients based on what nature has placed within their reach, from shellfish on our beaches and seafood caught by fishermen, to herbs still existing today, if you knew where to look for them.

The concepts of food as sustenance and medicine are explored in this section, too. Khir explores commonly-used techniques of preservation in Malay cuisine such as salting and fermenting – ingenious ways of extending the shelf life of ingredients in the tropics, especially in a time before refrigeration. The Malay system of traditional medicine is also revealed, in which many everyday dishes – the ingredients, how they are prepared and consumed – are actually preventive measures against potential illness.

A key highlight is the array of flavours in Malay cuisine. While it is generally accepted that there are five core tastes in cuisine — sweet, sour, bitter, salty, and umami, Malay cuisine features 12 flavour categories. Half of these categories are not perfectly translatable into English; “lemak” is a taste category unique to Malay gastronomy, as is umami to washoku (traditional Japanese food).

FOOD AND A SEARCH FOR IDENTITY

The inspiration for “The Food of Singapore Malays” is rooted in both Khir’s childhood in 1960s and 1970s Kampong Gelam, and later on in 1990s California where Khir went to university.

“Being away from family and home, you tend to examine and reflect on who you are,” he says. “I yearned to read in Malay, to taste the food of home, and to rediscover my roots.” He discovered that there were few books dedicated to Malay culture and cuisine, but in books on Southeast Asia, he would stumble across information about life in the Malay Archipelago.

Khir returned to Singapore in late 2007 after a six-year stint teaching mathematics in a California high school. He joined the Singapore Heritage Society where he started heritage trails in Kampong Gelam in 2010 as a way to get people interested in this historic district and its significance to present-day Singapore. “Kampong Gelam wasn’t just my childhood home,” he explains. “It was once upon a time a royal enclave, and the cradle of Malay culture in Singapore.”

Khir became increasingly aware that there is little documentation on Malay cuisine and its relationship with Malay culture, and the idea for “The Food of Singapore Malays” was sparked.

In the section Food as Civilisation, he explores the role of aesthetics in Malay cuisine, such as serving ware for different occasions and plating for festive feasts like nasi ambeng – food appeals not only to one’s sense of taste and smell, but also sight, and a dish must not only convey coherent flavours, bult also express coherent patterns. As with any culture, rituals and mythology in cuisine go hand-in-hand, and this is also highlighted in “The Food of the Singapore Malays”. The book ends with a section on Food and the Politics of Identity, an examination of how Malay cuisine today is the result of the region’s centuries-old global trade in commodities. Considering how shifting borders in today’s society might shape the future of Malay cuisine, Khir poses the question: What is Malay

cuisine today?

IT TAKES A VILLAGE

For over a decade, Khir Johari worked on “The Food of Singapore Malays”. “I was pretty much on my own,” he says. “With information so scattered, you have to be not just a historian, but a botanist, zoologist and anthropologist in order to connect the dots.

His other challenge: “In order to preserve what we have, we need to document. Sometimes, in order to document, we need to first reconstruct.” This spanned the gamut from regional trips to discover older foodways, testing recipes, fact-checking across multiple disciplines – and tapping the Malay community for help. Hundreds of people in Singapore, Malaysia, Indonesia readily contributed with photographs, anecdotes and even their homes once they understood that this book was meant to document their way of cooking and living.

“What began as a personal dream developed into a community project,” shares Khir. “What I hope the reader will find is the story of Singapore Malay food, stitched into a broader story of the people of the Nusantara (maritime Southeast Asia). Our own island is not only a recipient of the creations from all reaches of the Archipelago. It is a creative kitchen hub that continues to turn out its own interpretations of what it means to be delicious, and through that, what it means to be Malay.”

About The Food of Singapore Malays

“The Food of Singapore Malays: Gastronomic Travels Through the Archipelago”, explores in detail the history of the culture of Malay food in Singapore.

Written by Khir Johari, the book reveals how Malay cuisine has evolved to its modern-day form. Readers will discover how history, geography and cultural beliefs have shaped and influenced Malay gastronomy – and Singapore’s role as a creative kitchen hub in this culinary evolution. This landmark book celebrates not just the cuisine of the Malays, but the people and culture of the Malay Archipelago.

This book includes over 400 stunning photographs of food and culture around the region as well as 32 detailed recipes for key Malay dishes.

About Khir Johari:

Khir Johari, 58, is a respected Malay history and culture researcher and the author of “The Food of Singapore Malays: Gastronomic Travels Through the Archipelago”. More than a decade in the making, Khir’s first book is an exploration of the cultural anthropology of Malay food, and a showcase of how food has played a part in moulding Singapore Malay culture.