USD 3.7 trillion market for halal food, lifestyle

Experts, businesses and governments have talked about the immense opportunity for halal products and services for the global 1.8 billion Muslims worldwide. The latest Global Islamic Economy Report, commissioned by the Government of Dubai, has estimated the total spending on global halal food and lifestyle products is expected to reach USD 3.7 trillion by 2019.

Stopping the tide of halal in China and Australia

Despite talks about the huge opportunity for halal, we have seen backlash against the perceived inroad of “halal” in countries where Muslims are minorities such as in Australia and in China.

Kellogg’s and others withdraw from halal certification

In July 2017, Kellogg’s Australia has decided not to renew its halal certification, which means, its cereals produced in Australia including Special K, Crunchy Nut, All-Bran and Nutrigrain will no longer be certified halal. The decision was made not due to public pressure but due to commercial reason, said the company.

Another breakfast maker Sanitarium has followed suit by ditching the halal certification citing its products are already suitable for people wanting kosher or halal foods since no alcohol or meat-based ingredients are used.

From March 2016, all Nestle retail chocolate blocks and bars, and baking chocolate in Australia are no longer halal certified. Click here for the list of Nestle products that are still certified halal.

The anti-halal movements in Australia started gaining momentum in 2014 after an aggressive social media campaign forced the South Australian Fleurieu Milk and Yoghurt Company to ditch its yoghurt supply deal with Emirates. The backlash against the dairy firm came after it was known that the company was required to pay AUD 1,000 for the halal certification. There were suggestion that the halal certification fee would be used to fund terrorism and would pushed up the product prices.

Others including Reclaim Australia felt that the country is becoming increasingly “Islamified” and that the certification to obtain halal is a form of “religious tax.”

The number of Muslims in Australia reached 604,000 or 2.2% of the population, according to the latest census in 2016. This is almost doubled from 341,000 in the 2006 census.

Against the spread of “Halal generalisation” in China

In China, there is a term called 清真泛化 (qingzheng fanhua), loosely translated as “halal generalisation.” The terms is largely explained as the spread of the concept of halal beyond halal-certified food into other areas, while using the name of halal to meddle in the secular life of others” (泛化清真概念,将清真概念扩大到清真食品领域之外的其他领域,借不清真之名排斥、干预他人世俗生活的). This was one of the clauses in the anti-extremism regulation (新疆维吾尔自治区去极端化条例) approved by Xinjiang lawmakers on 29 March 2017 and went into effect on 1 April 2017.

A good example of the move to stem “halalnisation” is the replacement of the name to describe one of the restaurants in the Chinese aircraft carrier Liaoning from “halal mess deck” (清真餐厅) to “ethnic restaurant” (民族餐厅), which is now opened to all ethnic minorities.

Even before the enforcement of the law in Xinjiang in April 2017, Wang Zuoan, director of the State Administration for Religious Affairs (SARA), spoke about the creeping intrusion of halal into the daily life of the Chinese people at the China Islamic Association’s 10th National Congress in Beijing in November 2016. In recent years, there are examples of halal water, halal salt, halal flour and halal vegetables and how this halal concept has move into other areas like halal cosmetics, halal soap and even halal tissue in China.

There are calls within China to boycott halal-certified products citing the creeping Islamisation and the support for extremism from money spent on halal certification.

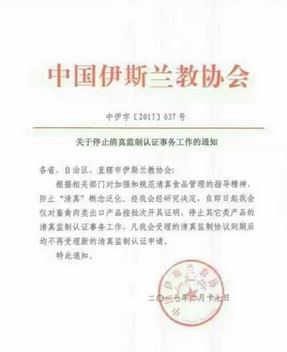

Islamic Association of China narrows its halal supervision to meat products bound for export

Following the change in the government policy, China’s biggest dairy company said in March 2017 that it would longer display the words “supervised by the Islamic Association of China (中国伊斯兰教协会)” next to the halal logo. The packaging will only display the word halal (清真). This comes after the Islamic Association of China issued a notice in March 2017 (关于不再续签清真监制协议的通知) stating the organisation will only provide certification for the export of meat products and not other products.

Popular food delivery app Meituan slammed

Meituan (美团网), the popular food delivery app in China, was rebuked by netizens after the platform announced in July 2017 that it would have different logistics infrastructure to handle halal food. The food delivery company planned to have two delivery boxes, one for halal and one for non-halal, resulting in outcry by netizens of discriminating against non-Muslims. Global Times, the English-language media owned by the Chinese government, reported that the “slogan implied that the food they eat is “unsafe and unclean.”

What Mini Me thinks

The lucrative halal market has attracted governments around the world to develop their halal industries. Taiwan, Japan, South Korea, Thailand and the Philippines are among the countries that are proactive in this area. Even Chinese companies are working to increase their exposure to the strong 1.8 billion Muslim consumers worldwide.

However, we see consumer backlash against halal in Muslim minority countries like Australia and China due to fears of Islamisation and the unintended consequence that the funds meant for halal certification would end up supporting extremism.

Companies operating in these markets should thread a fine line between halal and haram. Of course, they can still target the vast Muslim consumers worldwide with halal dedicated factories for the export market, while maintaining the non-overt display or even removing the halal logo for products meant for the domestic market.